By Ben Hess

Sixty of us panted in the thick suburban Atlanta August heat, bent over, hands on our knee pads, gulping for air. It was the end of another grueling practice, and we’d just begun the politically incorrectly named ‘suicides’ - a series of sprints starting from the goal line to the 50-yard line and back in groups of ten. After my group ran the first leg, we attempted to regain our breath and some semblance of control over our trembling legs. Then we were up again: sprinting down to the 40-yard line and back. And then we repeated, in 10-yard intervals down to the starting point. We were given two minutes to slurp ice-cold water before gathering around Coach L for his end-of-practice report, all of us on one knee, drained, and exhausted.

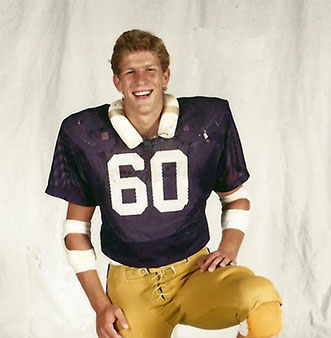

The temperature hovered between 90 and 95 degrees, despite that it was approaching 6pm, and the humidity pressed down on us like a Wisconsin-thick wool blanket. It was the fifth day of summer two-a-day high school football practice and our first day in full pads. Several of the sixty gangly, awkward 8th graders had never even played organized football until that week. In fact, we’d started the week with seventy players and lost ten to the grueling heat, demanding coaches, or both. There weren’t ‘cuts’ in the traditional sense. The coaches just expected timeliness and 110% mental and physical effort despite the heat.

Our team was different than those of years past. Not only were we larger in number, we were also more racially mixed than in previous years. My high school class represented the first large-scale implementation of a long-delayed, hotly debated "Majority-to-Minority" program, the roots of which grew from the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision. Following a host of litigation in the 60's, 70's and early 80's, it was ultimately decided that:

“The district court ordered the DeKalb County School System to expand its "Majority-to-Minority" ("M-to-M") transfer system of assignment, pursuant to which a student could transfer from any school in which his or her race was in the majority to a school in which that race was in the minority." (http://www.leagle.com/decision/1997789109F3d680_1667)

With M-to-M busing in place, my class became almost equally divided between Caucasian and African-American students. While we were still housed under the same roof as the dominantly Caucasian classes who came before us, incoming classes continued to see racial balance as the years progressed. Equally important for me and many in the community: we were continuing the school's tradition of winning football games, with successive appearances in the state playoffs. Several of our stars - both black and white - were recruited by leading southern Division I programs: University of Georgia, University of Florida, Georgia Tech, University of Tennessee, and Georgia Southern.

However, despite our on-field success as a team, and despite the fact that we had sweated, strained, and succeeded together from 8th grade through 12th, I can’t remember any of us whites hanging out with any of the blacks off of the field, and vice-versa. Instead, we followed the patterns of the student body at large - social behavior passed down from older classmates, siblings, parents and their parents before. We hung with our own racial groups during lunch, assemblies, before school, and after school.

Twenty years later, that prevalent social media platform called Facebook served as online glue and connected us prior to our October reunion weekend. I’d kept in touch with a core group of friends, but hadn’t seen the majority of my classmates since graduation all those years ago. And with the exception of posts and status updates, I hadn't been in touch with any of my black teammates.

The reunion was held at an upscale chain Italian restaurant, and I had to take a pause at the faces in the room. It was like Adobe had taken our senior class photos and run them through a time warp Photoshop filter: some folks in the room had less hair, others more weight, and all certainly displayed more maturity. More life lived. Sadly, though so much had changed physically, past patterns quickly repeated themselves in the large ballroom - the whites naturally went to the right, the blacks went to the left. And there we mingled and drank. Separately.

You see, I desperately wanted to learn about my black teammates; to bridge to our shared past; to make up for lost time. I wanted to hear about their lives, families, successes, and struggles. But I let the night slip by in a haze of drinks and talks with folks on the right side of the room. I used the frustratingly loud 80s music, the well-stocked bar, and the appearance of former classmate-turned Pulitzer prize winner turned US Ambassador to the UN Samantha Power as weak excuses for why we didn't mingle together as a unified group, even after all we had been through.

When the lights flickered at midnight signaling the end of our trip down memory lane, I hazily realized two things: I hadn't spoken with all the former players I wanted to and we hadn’t even been aware enough to get a group picture. I made a promise to myself that night - I will not let weak excuses stop me at the 30th Reunion. I’ll make those connections happen and, at the very least, get our photo taken. And between now and then, why not begin some of those conversations through social media and email? Life’s too short not to try.

Ben Hess is a proud Lakeside High School alum who now writes, produces, and directs video and marketing campaigns in the San Francisco Bay Area. Follow him on Twitter, @BenHess, for more stories.