By Peter Russert

During the last few months of my mom’s life I had two main thoughts about her. First I didn’t want her to have to suffer any more. I prayed that her body would just call it a day, and slip away silently during sleep. At age 90 she was in chronic pain, and could no longer get out of bed. Failing kidneys, fluid buildup around her heart and in her extremities, chronic pulmonary distress—I don’t think I can even rattle off all her “co-morbidity factors” as her doctor termed them. Thank god my aunt and I had finally found an assisted living home near the ocean in Venice, Florida that my mom had been willing to move into. During the last couple of decades she'd insisted on living alone in her own little apartment but she'd taken so many serious head-splitting falls over the previous two years that I was honestly surprised she’d survived. True to form, she’d tried to conceal all these episodes from me. Often I had to find out about them from my aunt, or the hospital. As I sat by her bedside in Venice she’d say things like, “I don’t understand why I’m still here. How do I keep going?” Of course with large stocks of hydrocodone right at hand my question was “Why do you keep going?” But that’s another matter.

My second thought was that her story would never be written. Not that her biography would have mattered much to anyone except me and perhaps a few of my cousins or their children. She didn’t set any world records, or marry anyone famous, or amass a fortune. But she did grow up in a pretty unusual and unusually batty (or was it just “colorful”?) family in Reading, PA. And that was only the beginning. I tried several times over the years to get her to at least sketch an outline of her story, bought her a couple of digital recorders in hopes that that would make it easier. But I wouldn’t have been surprised if she’d turned to me once and said, “Honey, some of those things I just don’t want to live through again.” Some of them were incredibly painful. I know, I lived through them with her. But about her childhood, the beginnings of her journey, I only got snippets and slices. So in an effort to try to grasp their deeper meanings I probably invented some myths. And yet when I tried some of these ideas out with one of my aunts, she said, “Yes, I think you’re probably right.”

There seemed to be two big forces at work in my mom’s life. The first was the lifelong search for a place, a role, a clear purpose. She was born Caroline Jean Vernon in 1922, the fourth of six children, to parents who were impossibly detached and remote, not to mention ill-suited to one another. I could poll my aunts up and down the line (I have): “We raised ourselves.” Jean, as they all called her, was sickly as a child. Her older, more self-assured sisters and brother had their own interests; her two younger sisters formed a tight bond that constituted its own little world. I think my mom was always baffled about where she fit in, and thus who she was in this peculiar drama. Who were her teammates? What part was she supposed to play? She had a strong love for her older brother, Stephen, who never minded including her in whatever he and his buddies were up to on weekends or summer evenings. “C’mon, let her tag along. She’s not going to be any trouble.” I inferred that the rest of them were too busy fending for themselves; if you didn’t, no one else was going to.

Of course, this is only one side of the Vernon family portrait. My mother and my aunts could tell endless farcical stories of their childhood—the word “circus” fit their collective life just fine. (Here’s a mere taste: my mom delighted in telling me about how my grandmother lived in books and loved to do nothing more than retreat to the library and read, regardless of the chaos throughout the rest of the house. While she read she enjoyed eating a well-know local brand of chocolates. My mother and her sister Lolly liked to sneak into the library to sample these candies. When they took bites out of ones they didn’t like so much, they’d neatly put them back into their wrappers in the box. These were dubbed “spitbacks,” and to underscore my grandmother’s abstracted nature Jean told me that Granny would pop a spitback into her mouth while reading and never miss a beat. I often got the impression that their family life was just a huge mashup of mischievous bits like this.)

The second force in my mom’s life was an enduring sense that no matter what she tried or what she chose, things were going to go wrong. I don’t think she cultivated this sense of doom, or wanted anything to do with it. Stuff just happened. And kept happening. Kept pounding the message of futility into her until she capitulated. Maybe bad stuff happened to people who were uncertain of their places or senses of purpose?

In her late teens she fell deeply in love with a local boy named Howard Lutz. As I heard the story, he was just as crazy about her. They talked about getting married—at least until the day he arrived at the house and told her that while he was still very much in love with her, he had to marry another girl who “couldn’t survive without him.” He “couldn’t let her down.” I always took this as code for “Jeannie, I’ve gotten another girl pregnant—what can I do?” My Aunt Lolly said Jean was devastated. But it couldn’t end there, of course. Not long afterward Howard enlisted in what was then known as the Army Air Force (this is the beginning of World War II), and was killed in a training accident in Pensacola. If you flip through my mom’s papers you’ll find old sepia-toned photos of him. In one he is emerging from a swimming pool, laughing, his dark hair slicked back. And he’s beautiful, by any standard. I could easily understand how deeply smitten—and wounded—she’d been.

It was bad enough to have the outside world throwing defeat at her, but her own mother got into the act. I’d known in my youth that my mom had spent time in Coast Guard during World War II; I’d seen the pictures. But her stint in the service took on a different significance once I’d grasped her craving for a mission. She loved the Coast Guard. She took her share of hazing from the guys she was stationed with in Palm Beach, but a letter of commendation makes clear that she manned her radio post with valor during a hurricane. She spoke glowingly about her commanding officer and how much he’d taught her, what a great mentor he’d been. Perhaps there was romance there too? “He took me all over Miami, and really opened my eyes to what was happening there.” After the war she returned to Reading. Meanwhile her commanding officer had sent a letter to her encouraging her to re-enlist. She told me she would have done it in a heartbeat. But she never saw the letter, at least not until long afterward. Her mother had read it herself and kept it from her—because having a meaningful life with the possibility of advancement was a bad thing for her daughter? This floored me.

Then, somewhere in this time frame, her father killed himself. I never knew what to make of this episode, or its impact on my mom in particular, because it was always shrouded in mystery. He was shrouded in mystery. Was he terminally ill, or did he fear, as I once heard, that he might be following his own mother’s footsteps into insanity, or…? Or he was simply depressed? The event had one kind of impact on two of my aunts who heard the gunshot in the library, and found him with a bullet in his head. But my mother was en route home at the time. She never wanted to say very much about it.

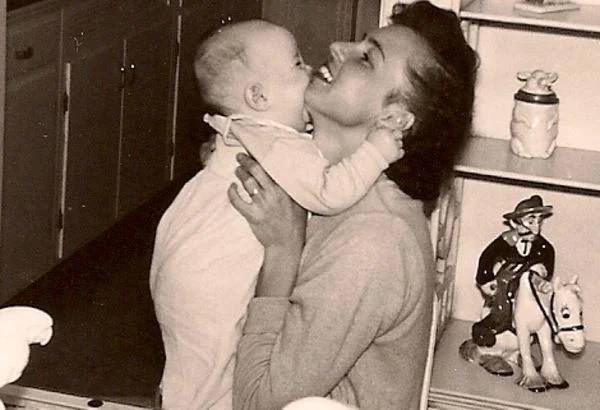

She soon returned to Miami, fatefully enough, to become a flight attendant for Eastern Airlines. But she was chronically airsick on those old DC-3’s. “The stewardess who was too busy throwing up to help anyone else,” she laughed. “Well, there you have it…” That lasted a year maybe. Back on terra firma she met my dad, got into the hotel business with him, and had me. And yet while I was still a toddler she was obviously beset with doubts. To the point of crisis, apparently. Once again my grandmother came into the picture. My mom told me she just wanted to pack up, grab me, and escape from Florida. She asked her mother whether she could return to Reading to stay with her until she sorted things out. My dear old granny told her, “Absolutely not. You made your bed down there; you can lie in it.” This sounded incredibly cold and vindictive to me when I first heard it, but I figured out later that it simply reflected my grandmother’s old-school conception of marriage as an ironclad social contract. No matter how miserable you thought you were, you just couldn’t run away. You had to tough it out.

And so she stayed and toughed it out. In fact she had a second child with my dad, a daughter named Anne. She may have bought the idea, as I know some parents did in those days—and maybe still do—that having another child would help settle her marriage and bring more normalcy to our dysfunctional collective life. Not this time. When she was about three my sister somehow contracted meningitis. I don’t know how long she was really sick, or how meningitis works, but it seems to me that she was in trouble for a couple of days, and then suddenly died at home in her bed. I’m sure my parents were clueless at first about the seriousness of the illness—I’m guessing it seemed like flu—but on the Saturday my sister died she was vomiting some very dark stuff, and my mom knew she had to be seen by a doctor. She called my dad. He told her to bring her to the hotel he managed on Miami Beach; there was a “good doctor” who was a guest who was willing to look at her. The good doctor misdiagnosed the illness—I half want to write “of course.” That was early afternoon. When my dad got home at about six, my mom asked him to go upstairs to check on my sister. By then her lips and her fingertips had turned blue. I know; I saw her body.

I won’t say much more here about my mom’s grief—my parents’ grief; it doesn’t need elaboration. Or even her unbearable sense of responsibility for the loss of someone so young and vulnerable. She carried this guilt with her for the rest of her life. But beyond this, she seemed in her own mind to just get further affirmation that whatever she loved was fated to go wrong. That whomever she loved was going to be taken away from her. That she lived under some sort of curse.

Our family more or less fell apart from that point forward. But Jean went on. I realized over time that she had a very deep capacity for love and even for forgiveness. She married again, twice. Both husbands died during the marriages, but on the whole they were very happy times. (Don’t worry, we covered all the jokes about “No more marriages, no more dead husbands!”) Jean was in love, she got to travel widely, make a lot of new friends, and feel fulfilled. But there is another scene that comes to mind here—this was in the mid 1980’s when she was taking care of her own dying mother. In fact the scenes of my mom ministering to my grandmother at her bedside are uncannily similar to my own presence at my mother’s side just before she died. It was a little different though in the sense that my mom had done nothing in her life that I could be bitter about. My grandmother had never been a real mother to her children. She had overruled, and even manipulated my mom, maybe more often than I knew, and certainly with some arguably tragic consequences. Did my mom ever think, “You wouldn’t let me come home; if I’d been able to, I never would have lost a child!” And yet I remember my mom doing everything possible to make her mom comfortable. My grandmother was 93 by then, and had been silenced and incapacitated by a series of strokes. She could do little more than lie in bed and stare quizzically. My mother brushed her hair, gave her sponge baths, fed her, caressed her, and spoke to her as if she were a little girl passing through a childhood illness. I don’t know why Jean, among all her siblings, took on this task, but it was quite amazing to observe.

I never gave my mom the love she deserved. I was too busy getting away. I grew up feeling a strange (and illusory) sense of autonomy, and disconnection from both of my parents, their anger, quarreling, and visible unhappiness. Several times my mom used that infamous phrase, “I always thought you were the real adult in the family.” Of course I didn’t really want to have to parent my parents, although once or twice it seems I actually had to break up fights and send people to neutral corners. On the other hand, I was glad to escape dependency on both of them as much as I could. I think my mom got this; I’m not sure she even had to bear it stoically. She might easily have said to me, “Hey, getting away is what we do. Maybe its just in our genes. Your dad was the youngest in his family, and he couldn’t wait to escape from home. Even I tried to run away as a child…” which was an amusing story in its own right.

My mom not only understood my desire to escape; in a weird way it gave her strength and happiness. In her myth, I was the one who made it out alive, the one who proved she had done something right. She was sure I had “made it,” that my life was some huge success story, and while this was mostly illusory, I had no interest in puncturing the illusion. Over the final few months she’d told me countless times, “I don’t want to disrupt your life; I don’t want to be a bother. You’ve got big responsibilities in your own family.” I said, “Don't be absurd,” and got on a plane to head to Florida whenever I needed to. We had never seemed very close emotionally, and certainly not outwardly affectionate, but in her final days, I was by her side, holding her hand, bugging the hospice nurses to give her extra doses of morphine. And telling her I loved her. Once, during her last hour or so, her eyes flashed open, and she more or less cried out, “You were my first born and always closest to my heart!” Then she drifted right back into unconsciousness. I was startled by this, especially in light of my sister. But I think I knew what she meant.