These stories talk about guilt.

We’re not proud of everything we’ve ever done. Or we regret actions we didn’t take. We can make ourselves feel guilt, or others can place it upon us. Guilt is a common emotion that we each deal with differently.

These stories talk about guilt.

We’re not proud of everything we’ve ever done. Or we regret actions we didn’t take. We can make ourselves feel guilt, or others can place it upon us. Guilt is a common emotion that we each deal with differently.

By Josh Leskar

In 2010, the summer between my junior and senior years of college, I finagled my way into traveling around the world, mixing in two studies abroad for some educational justification. Over the course of my three-month adventure, I made it to nine countries on four continents and met some of the most fantastic people along the way. To this day, that trip remains one of the most inspiring, life-altering trips of my life.

For the majority of my journey, I studied the social, political, and economic factors that the FIFA World Cup was having on the nation of South Africa, and in an attempt to immerse the students most fully, our program assigned each student to live with a host family. Living situations differed – some homes had two parents, many had one, a few had brothers and sister and, in one case, a student was older than both of her host parents.

I was paired up with my “Gogo,” or grandmother in Zulu, who was not only my grandmother, but was also the matriarch for the entire community. She was an elderly, heavyset woman with two different colored eyes, stern and firm in her ways. Yet from the moment I crossed the threshold of her cozy home in the city of Durban, she welcomed me, quite literally, with open arms. For the entire duration of my stay this amazing woman, living on a government pension, was as motherly a figure as one could imagine. She sent me off each morning with a piece of fruit for breakfast, cooked me dinner every night, washed my clothing when it didn’t need to be washed, and cared for me as if I were her own child.

We spent evenings watching soccer matches and soap operas in a language I couldn’t understand, chatting about politics and our family histories, and sharing stories about our lives on opposite ends of the world.

Parting ways brought tears to both of our eyes, and I vividly remember her insistence on carrying my bag from our house out to the car the day I left, even though it weighed entirely too much for her to lift.

And we haven’t spoken since.

This is nothing new: I’m a victim of immediacy, which is not to say I’m innocent. I’m closest to those nearby, when it’s most convenient for me. This trend is one I’ve found in my existence as a human being – the sociable person I am, I can never manage to maintain a consistent relationship with anyone who isn’t within close physical proximity. Not out of malice, but rather I simply let even the minutest obstacles keep me from completing the simple task of communicating with someone far away. Their address is in my notebook somewhere buried in the closet. I don’t have any thank-you cards. I have to set up a paid Skype account.

I often ask myself if it’s worth the effort to maintain contact with someone – and even that thought riddles me with guilt. From a logical standpoint, it comes down to a tradeoff between the joy a person brings into your life and the effort expended to achieve that joy.

The way I see it, these people have given so much to me – their time, their friendship, their love – that the five minutes it would take for me to write a letter, the two minutes it would take to make and complete a phone call, or the thirty seconds it would take me to send a measly email each seems like so insignificant a gesture that I’d be a complete jerk not to make the effort. Yet time and time again, it becomes too much of a hassle for one reason or another, and the more time that passes, the harder that gesture becomes.

So many people enter and exit your life, fleeting specks in the grand scheme of the world. Others stay and develop relationships that exponentially intensify in a beautiful coalescence of genuine compatibility. Often times, it’s hard to discern who will have the most lasting impact, and who will merely vanish into a distant memory as a temporary product of circumstance. For me, the problem persists because I always pour my heart and soul into every relationship, but once it becomes remotely difficult to maintain, I tend to abandon ship.

Perhaps I’m too egotistic, thinking I’ve had a significant impact on the lives of others I encounter: that my presence in their lives has any impact that is somehow so meaningful to them. It’s entirely possible that they quite frankly couldn’t care less about me, or worse, don’t remember I even existed. When my guilt hits hard, I like to believe this is true.

In my heart of hearts, I doubt it.

In the time it took me to write this article, I could have sent Gogo a gift, written her a letter, picked up the damn phone and called to let her know I’ve been thinking about her constantly for the past three years.

But I didn’t. And to be perfectly honest, I probably wont, for one excuse or another.

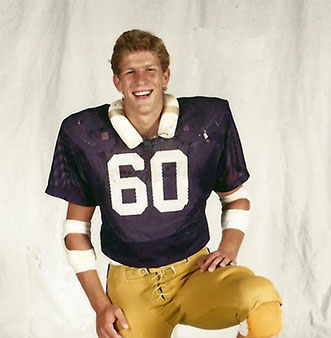

By Ben Hess

Sixty of us panted in the thick suburban Atlanta August heat, bent over, hands on our knee pads, gulping for air. It was the end of another grueling practice, and we’d just begun the politically incorrectly named ‘suicides’ - a series of sprints starting from the goal line to the 50-yard line and back in groups of ten. After my group ran the first leg, we attempted to regain our breath and some semblance of control over our trembling legs. Then we were up again: sprinting down to the 40-yard line and back. And then we repeated, in 10-yard intervals down to the starting point. We were given two minutes to slurp ice-cold water before gathering around Coach L for his end-of-practice report, all of us on one knee, drained, and exhausted.

The temperature hovered between 90 and 95 degrees, despite that it was approaching 6pm, and the humidity pressed down on us like a Wisconsin-thick wool blanket. It was the fifth day of summer two-a-day high school football practice and our first day in full pads. Several of the sixty gangly, awkward 8th graders had never even played organized football until that week. In fact, we’d started the week with seventy players and lost ten to the grueling heat, demanding coaches, or both. There weren’t ‘cuts’ in the traditional sense. The coaches just expected timeliness and 110% mental and physical effort despite the heat.

Our team was different than those of years past. Not only were we larger in number, we were also more racially mixed than in previous years. My high school class represented the first large-scale implementation of a long-delayed, hotly debated "Majority-to-Minority" program, the roots of which grew from the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision. Following a host of litigation in the 60's, 70's and early 80's, it was ultimately decided that:

“The district court ordered the DeKalb County School System to expand its "Majority-to-Minority" ("M-to-M") transfer system of assignment, pursuant to which a student could transfer from any school in which his or her race was in the majority to a school in which that race was in the minority." (http://www.leagle.com/decision/1997789109F3d680_1667)

With M-to-M busing in place, my class became almost equally divided between Caucasian and African-American students. While we were still housed under the same roof as the dominantly Caucasian classes who came before us, incoming classes continued to see racial balance as the years progressed. Equally important for me and many in the community: we were continuing the school's tradition of winning football games, with successive appearances in the state playoffs. Several of our stars - both black and white - were recruited by leading southern Division I programs: University of Georgia, University of Florida, Georgia Tech, University of Tennessee, and Georgia Southern.

However, despite our on-field success as a team, and despite the fact that we had sweated, strained, and succeeded together from 8th grade through 12th, I can’t remember any of us whites hanging out with any of the blacks off of the field, and vice-versa. Instead, we followed the patterns of the student body at large - social behavior passed down from older classmates, siblings, parents and their parents before. We hung with our own racial groups during lunch, assemblies, before school, and after school.

Twenty years later, that prevalent social media platform called Facebook served as online glue and connected us prior to our October reunion weekend. I’d kept in touch with a core group of friends, but hadn’t seen the majority of my classmates since graduation all those years ago. And with the exception of posts and status updates, I hadn't been in touch with any of my black teammates.

The reunion was held at an upscale chain Italian restaurant, and I had to take a pause at the faces in the room. It was like Adobe had taken our senior class photos and run them through a time warp Photoshop filter: some folks in the room had less hair, others more weight, and all certainly displayed more maturity. More life lived. Sadly, though so much had changed physically, past patterns quickly repeated themselves in the large ballroom - the whites naturally went to the right, the blacks went to the left. And there we mingled and drank. Separately.

You see, I desperately wanted to learn about my black teammates; to bridge to our shared past; to make up for lost time. I wanted to hear about their lives, families, successes, and struggles. But I let the night slip by in a haze of drinks and talks with folks on the right side of the room. I used the frustratingly loud 80s music, the well-stocked bar, and the appearance of former classmate-turned Pulitzer prize winner turned US Ambassador to the UN Samantha Power as weak excuses for why we didn't mingle together as a unified group, even after all we had been through.

When the lights flickered at midnight signaling the end of our trip down memory lane, I hazily realized two things: I hadn't spoken with all the former players I wanted to and we hadn’t even been aware enough to get a group picture. I made a promise to myself that night - I will not let weak excuses stop me at the 30th Reunion. I’ll make those connections happen and, at the very least, get our photo taken. And between now and then, why not begin some of those conversations through social media and email? Life’s too short not to try.

Ben Hess is a proud Lakeside High School alum who now writes, produces, and directs video and marketing campaigns in the San Francisco Bay Area. Follow him on Twitter, @BenHess, for more stories.

By Danie D. Taylor

At this moment, in early 2014, I have three brothers and two sisters. I note the year because I have learned how quickly that number can change. Ten years ago I had two brothers. Compared to other friends currently in their 30's, my Sibling Growth Rate (SGR?) borders on incomprehensible. But it wasn't always this way.

There were only two of us growing up, Danie & Derek. We were together from the time Derek was born until I went to college. Derek and I developed a relationship that worked for our personalities. We didn't like a lot of fluff. Our formal regard for one another bothered our parents. They used to demand to see us hug when I came home from college. In those instances we would pour it on, squeezing each other and pretending to be overcome with emotion. The parents were not amused.

Derek and I haven't lived together in 16 years and still, I know what bothers him and when he needs tough love as opposed to blind support. Even now, we rarely talk about our feelings or say "I love you." Like any siblings, we have the bond that comes from surviving parents and sharing history. We also share guilt.

One winter break, while snooping through my dad's things, Derek found a sonogram. It was a recent image of a Baby Taylor. It was right before my dad’s birthday, and I don’t think he was surprised to find condoms in his gift bag that year. Four months later, Ty was born. He was eight months old before I held him (as I was leaving the country to study abroad). He took his first steps before we spent a single night under the same roof.

Unlike myself or Derek, Ty has always been extremely expressive. He loved his absent siblings immediately and acted accordingly. One of my first Ty memories is - after arriving late one night at my dad’s - waking up to Ty's face inches from mine. I opened my eyes. He exclaimed, "Hi Danie!" and launched himself at me.

Weirdo.

Precious.

Ty and I never lived together. I graduated from college and moved to Fargo, then Las Vegas and finally San Francisco. He lived with his mom in North Carolina. I would call, but the list of discussion topics between a 20-something girl and a boy under 10 was limited. Thank God for Ben 10. Seriously.

The only person who could remotely understand my feelings regarding Ty was Derek. Because, you know, the sibling survivor bond and all that.

First of all, we were angry. We didn’t want another sibling. We didn’t want another “D. Taylor” sharing our name without having earned it. We did not want to split holidays or have to coordinate with another family. We honestly didn’t understand why we even had to acknowledge the baby. My dad has at least four half siblings I literally cannot name, and one we knew for a few months who was named after my grandfather. Basically, I was a terrible, bratty teenager reacting to disruptive news. It was a lot worse for Derek.

“You don’t understand Danie,” he told me. “It’s not another daughter. It’s another son.”

To Derek, Baby Taylor represented another son who could make up for any of Derek’s (perceived) shortcomings. He was a kid worrying about being replaced. As his champion, I took up his cause. The whole thing was a dramatic fiasco that no one needed. How dare our father bring this to our door?

Righteous indignation is fine, until a little squirming person is presented to you. When someone hands you a baby and declares him (in any way) yours, well, all bets are off. I wrapped Ty into my protective life bubble. He was mine to love and support, a new recruit to team Danie-Derek.

Wanting the best for a family member is the easiest way to let the guilt get you.

Our father put us in a position for which we were not prepared. He knew remote fatherhood. We did not know remote sibling-hood, other than to know it was a responsibility. We weren't there with or for Ty for the dissolution of the relationship between his mother and our father. Though Ty didn't know he needed us, he did. And Derek and I knew it. Ty needed the user's manual to our father that Derek and I devised. Our dad is a sensitive sort, when he's not being a brute. Ty had to learn on his own. What good is having older siblings if they don't pave the way for you? What kinds of siblings abandon the youngest among them?

Ty's mother could not provide the same kind of life Derek and I had when we were little. He had everything he wanted, but he didn't go to private school - which (misguided or not) Derek and I had been taught was the first step to success. His mother was alone with three kids. Our father was a long drive away. Ty never had family game nights with us and he missed, "time to get on daddy," which was the battle cry when Derek and I would team up for a tickle take down of the big guy. (Once he was down, we would sit on him, obviously.) Ty has almost always had two separate parents. That wasn't fair. Derek and I felt that put him at a disadvantage. We could have tried to compensate by visiting him without our dad. We could have called more. We could have done homework with him over the phone. We could have done anything to be there for him. But we didn't. As the oldest, I didn't. I needed to tweak my sibling approach for this affectionate and eager new audience. But I didn't know how. And I never made the time to learn.

After the anger and along with the guilt, Derek and I were resigned. Part of our unity comes from logical calculations. While our parents are balls of emotion, Derek and I are cold - or "practical" if you feel like being polite. The fact was that we didn't sign up for a lifetime commitment to our father's weekend fling. We could not be expected to change our life plans out of guilt. I could have moved back east to be closer, but I wanted to be west. I could have set up a weekly phone call, but how long before it became a chore? I could have chipped in for the education I wanted him to have, but that wouldn't be fair to me. There was little Derek and I could to "improve" Ty's “situation.” No, there was nothing wrong with his life. It just wasn't the same as ours. Derek and I told each other we would do what we could, without trying to parent. We never clarified what that meant, but it felt like a resolution we could keep.

Four years ago, Ty's mom moved their family to southern California. I imagined the opportunities of being in the same time zone and in the same state. Calls. Visits. Things were going to be glorious! Until they weren't.

I called more often, for a while. Ty came up here once, more than three years ago. I saw him for a trip to Mexico, and the last time we were all together for Christmas 2012. He’s still delightfully intuitive. After hearing about my breakup with XBFJ, he asked, “Did he take his Xbox?” Then, “Did it hurt?”

I don’t know how this kid landed in my family.

We are talking about a sister fail of epic proportions. How is it I can go to South America for 19 days, but I can't bring my brother up from SoCal for a weekend of SF fun? He's not a baby. We can talk about all kinds of things now - including the fact that Ben 10 Omniverse is terrible. My dad told me his voice is changing. I still haven't called to hear it. Do I need another reminder of the childhood I'm missing? Would it be the impetus I need to change my ways and be the sister I should be? Or would it add to the shame that has so far kept me in the shadows of Ty's upbringing?

There's only one way to find out.

By Margaret Castaneda

About a year ago, my EMT partner and I were sent to a unknown medical emergency at a library. As we walked in, the fire guys were standing by the men's bathroom door. The lieutenant walks up and said "Ok, here's the deal.” In my head, that meant we we're in for a doozie.

An elderly gentleman drank some chocolate milk before making the 1/2-mile walk to the library. Once he arrived, his stomach turned against him and he had a bout of diarrhea. Embarrassed, the man asked the librarian for help. He had walked from his home and he had left his wallet there. The librarian dialed 9-1-1 for assistance.

Dispatch sent a firetruck and us. The lieutenant explained that they had cleaned him up and placed his soiled clothes into a bio bag. The gentleman did not need medical assistance; he just needed to get home. I looked at this man standing in the bathroom with paper pants and a walker. The smell was intense, but I kept thinking, “This man needs a break.”

I assured this man and the fire guys. “It shouldn't be a problem. I'll clear it with dispatch.” That's where I was wrong.

I asked our dispatcher if we could be out of service to take the man home, just blocks from the library. She told me she would call me back. I received a call from my supervisor telling me, per our company’s owner, to hand the man a blanket and go back in service.

My supervisor was a straight up guy, I explained the situation and he said he understood, but that the owner said no dice. He argued, as I was in uniform, I represented the company, and we could not be giving rides to homeless guys because we were not a taxi service.

The man in the library could not get a cab. He had no money and no wallet. I asked if dispatch could call a taxi, and said I would pay for it. Again, I was reminded that I was in uniform... blah blah blah. My supervisor eventually gave me the phone number, and I called. He also allowed me to get "lost" for 20 minutes, so that we could wait with the man for his cab. My partner explained everything to fire and they left. We waited.

I jumped in the back of the ambulance to grab this man a blanket. I broke down and cried. I was so angry and disappointed. How could I work for a company that could be so callous towards a human? He was not homeless. He had no family or children and he was alone. That's why he first went to the library, he was lonely. I would never want any of my family members to be treated that way. And as far as my being in uniform, was this the way the owner wanted the company represented?

The cab finally showed up and we explained the situation to him. He helped the gentleman into the front of the cab. I gave him $10 and apologized for not being able to take him home. He said my partner and I had done more than enough.

For the rest of the shift, my partner and I talked about what happened. We were not EMTs because of the pay. It was because most of us want to help people. EMTs are there when people are at their worst. We do have gallows humor and probably have THE most inappropriate death, blood, guts and poop conversations over dinner, but we are human.

At the end of our shift, both the owner and the President of the company were in the ambulance bay. The president looked at me and said, "Well if it isn't our very own 501c3 girl. Help out any more homeless guys?"

I decided I no longer wanted to work there. I could take the poverty level pay, the consistently changing horrible hours, the good and the bad partners, but the lack of humanity was more than I could bear. I hope neither of those men ever grow old and shit in their pants...karma sucks.

By Tanya Rose

How do you begin to tell the story of your dad (the first love of your life, if you’re a girl)?

These memories flash in front of me. When I was little, I would puff up my chest when he came to pick me up from daycare, because I thought he was the most handsome out of all the dads.

Later, he set up a new telescope at my birthday slumber party, thinking it would be a hit with the girls, but it wasn’t. I felt bad for him, because what he did was really sweet. He was sweet. So I went outside and the two of us looked at constellations.

When my mom had cancer and my little kid brain didn’t understand, he made me feel safe. And then decades later, when he was in the hospital fighting for his life, I wasn’t, and never would be, prepared for him to go.

He just lay there, machines breathing for him. Doctors asked us if they should bring him back should his heart stop, and my mom turned to me and said, “I don’t think he’s done living yet, right? I mean right?” She was lost. My dad had always made the tough decisions.

I don’t know much about my dad’s life before me. I know that he’s one of eight kids and grew up on a farm in Kansas. I know he was bookish while his brothers and sisters were athletic. I know he joined the Air Force and served in the Vietnam War, and that the GI Bill made it possible for him to go to law school. I know he was studying for the Bar Exam when he met my mom on a blind date.

But I don’t know any of his friends from when he was a kid, and I don’t know if he had girlfriends before 1973.

The post-me version of him, the one I know well, dreamed big, but at the same time, was satisfied with the cards he’d been dealt. He had two daughters (no son, and never once has he complained) and ran a small law practice up until he retired in the mid-2000s.

He was the lawyer who talked a couple out of getting divorced, the guy who visited the town drunk in the hospital after he’d broken his hip in a fall, the man who hired a meth addict as a secretary because she came from a good family and was trying really hard. I asked him once why he does these things, and he shrugged and said, “It’s just the way I is.”

But he is also the guy who drove when the doctor said he shouldn’t (he called a locksmith when my mom took away the keys). Who once got in trouble for laughing at a prosecutor who’d made a ridiculous argument.

When I was in high school, he would help me write editorials for the school paper. Mostly, he’d talk me through ideas. I think my love of newspaper reporting came from those conversations at the kitchen table where he’d pull out a clipping and start talking.

In 2005, he called me at work and told me he wanted to give me his oak office credenza when he died. He had put it in his will, and he wanted me to know that he’d picked it especially for me.

By then, I was living in California, and hadn’t been back to Kansas in a couple years. He was always bringing up weird things at weird times, so I tried to chalk it up to that. But an hour later, I was standing in the break room heating up a Lean Cuisine and I started to cry. I booked a flight home that day. And when I got there, he was fine. No ailments to speak of, no problems. He’d just been planning ahead, and wanted to make sure the credenza was OK with me – that I felt my sister and I were being treated equally.

My sister was the one who called me in 2011 to tell me my dad was hooked up to a ventilator.

To say I wasn’t ready for this news is such a cliché. I could go on about how unprepared I was, how I sat there in denial while she filled me in (he’d started hallucinating and it freaked my mom out enough to take him to the doctor. Hours later, he was being flown to Wichita.)

They put him in ICU, where he would stay for two months, unconscious.

These things had put him there: COPD, a couple decades of chain smoking, a lot of extra weight around his belly and a paralyzed lung. He hadn’t been getting enough oxygen for quite some time and the doctors said that if my mom hadn’t taken him in, he likely would have suffocated in his sleep that night. They said he would eventually need a tracheotomy in order to live.

We don’t know very many people in Wichita. So we all – me, my mom and my sister - crammed into a hotel room a couple miles from the hospital, and each morning, we’d make the pilgrimage to his room where we would sit and wait.

Days passed. Sometimes he would start to come to, and he would cry. But he couldn’t talk, not with a ventilator in his throat, so we didn’t know what he was trying to say. Before this, I’d seen him cry but once — when my cousin was killed at 15 in a motorcycle accident. I was only 6 then, and it was the most unsettling thing I’d seen. My dad was the strongest person I’d known, and here he was years later, crying a second time — strapped down, confused, frustrated, sick.

I had just started a new job with no vacation time, so I couldn’t stay in Kansas forever. I hate this, but it’s one of those hard realities that people don’t understand unless they’ve been there. I had no one to lean on financially, and life does not stop. Eventually, I had to get on a plane and go home, not knowing if I’d ever see him again.

I am a horrible daughter for leaving my mom in that situation. I imagined her at the Panera Bread Co. across the street from the hospital, getting soup for lunch every day by herself, then calling me with updates.

I remember standing in the middle of the Alameda County Fairgrounds on my cell phone, trying to talk to her over the shrieking of children high on deep-fried jellybeans (I was there reporting a story). I heard “brain damage” and “possible stroke” while staring right at the Michael Jackson funhouse. What crap I was in that moment.

They performed the tracheotomy. He came to, and ripped it out, doing a lot of tissue damage in the process. Eventually, he started breathing on his own, miraculously. The tracheotomy damage healed. He went to rehab. He lost 80 pounds. He came around.

Today, two years later, he breathes better than he has in years. And there’s no sign of the tracheotomy, other than a scar on his neck. No brain damage either.

He doesn’t remember much about what happened – only bits and pieces. A few weeks ago, my sister and I went to Kansas to throw a surprise 40th anniversary party for my parents.

My mom bawled. My dad had a ball. He says he was surprised, but I doubt this — he showed up to what was billed as a Wills and Trusts lecture (the best ruse we could come up with) in a snazzy suit, AND he’d gotten a haircut. Someone spilled the beans. But it didn’t matter – we watched him visit with longtime friends and his brothers and sisters, laughing and telling his sometimes very long stories.

I definitely thought of this party as a “Thank God you're still here, let's celebrate while we can” kind of thing. But a friend pointed out to me the other day that it could have meant something entirely different when it came to my mom. Of course it was to celebrate her too. But it was also my way of saying, “I'm sorry I left you like that.”

When it comes to my dad, there are echoes of 2011. He gets winded walking too fast. And two-plus years later, he’s gained back most of the belly. I asked if he’s eating OK and he dodged the question, saying only that his family genes are strong. My heart breaks, because I know that someday, we will go through some form of Wichita all over again. But we did get a second chance, and for that, I’ll always be grateful.