The stories on this page talk about losing a loved one.

A painful experience that can either destroy or inspire those left behind. Regardless of the "how," or the "why," losing a loved one, has the power to change us.

The stories on this page talk about losing a loved one.

A painful experience that can either destroy or inspire those left behind. Regardless of the "how," or the "why," losing a loved one, has the power to change us.

by Margaret Castaneda

My partner and I were just finishing up dropping off a patient at a nursing home when we received a call from dispatch. Our pediatric unit was picking up a patient and needed a pediatric transport from an emergency room nearby. Our dispatch warned my partner that the call would probably be needed to be upgraded to a Code 3 (lights and sirens).

We made our way to the ER, and nothing could have prepared me for the way this call would change my life. I walked into the trauma area and saw a woman with wet hair. She looked familiar and was staring into the room. Her eyes were bloodshot from what I can only imagine were the most painful tears a mother can cry. I walked in, and saw a small child laying on the bed, a nurse doing compressions, the doctor yelling for instruments to intubate, and controlled chaos all around me.

My partner asked that I get the mom in the truck and ready to go, so when the pediatric team was ready, we would load and go. I remember having no words to say to this mother. I have always been able to be compassionate with patients, especially their parents, but I had no words. I knew the look of death. I could not console, she too knew the look.

The little girl had been in the backyard playing, when she somehow fell into the pool. When her Mom found her, she jumped in the pool, pulled her out and started CPR.

The whole ride back to the children's hospital, I could hear her mom yelling at cars to get out of the way. The sirens were blaring and the monitors were beeping, and I stared at the little girl's wet hair. I helped effortlessly, as if it was just another patient. My partner and I didn't really talk the rest of our shift, except to say that we were going to have a drink after work.

by Erin Dwyer Paglione

It has been one hell of a year, well two years really, but this year was extremely rough. In December 2012 my dad was diagnosed with Stage 4 lung cancer. I was 6 months pregnant with his first grandchild and living in Denver after taking a new job and moving my entire family from Los Angeles. My dad and family all live on the east coast so I’ve been “away” for 13+ years.

Initially the diagnosis felt like a punch in the stomach, even though we had known my dad wasn’t in the best of shape since my wedding two years earlier. My dad seemed to have his worst health ailments around my major life events it was our little joke. His lung collapsed the day of my wedding shower and I remember being in tears, shock and also numb that day. I remember hearing “he may not make it more than 5-10 years.” But then you forget that. You feel safe again; you think it was a fluke. You go back to normal. You stop calling as often and you stop making that extra effort because, well, Life.

Fast-forward 3.5 years and reality was facing me. My guilt was facing me. My fear was facing me. No matter how much you prepare or expect or know something may come – your heart and brain cannot comprehend it. Not even after it has happened.

After my dad’s diagnosis we went through a variety of emotions. Feeling like we just wanted him to be out of pain, and for us to be out of the fog that is the non-committal cancer diagnosis and treatment process. There was nothing more frustrating than the continual lack of definitive information. No one knew if the treatment was really working, if the new plans had any potential hope or how long he really had. I hated the doctors and I loved the doctors. I hoped and wished that my dad would meet his first grandchild. Even more, I hoped and wished that he wouldn’t pass when I was unable to travel to him.

We were so lucky. We got all of that. My dad’s first round of treatment was “successful,” however, that word’s meaning in cancer treatment is not the same as the definition in Webster. “Successful” meant the tumor shrank and responded to the radiation. That bought us time and time meant everything to me and my family. Time allowed me to see my Dad light up at the sight of his granddaughter, something that will be with me for the rest of my life. Time gave my dad the ability to stand next to his son as one of his “best men" on my brother’s wedding day. Time allowed me to write my dad a letter to tell him all the ways he’ll be remembered, all the times that we will think of him, see him and feel him with us.

The hardest part for me when we received his prognosis of six months was facing the fact my dad had to face death. I didn’t know how to comfort him or contemplate that. What an impossible and difficult process for someone. To be looked in the eye and know that is imminent. And while hospice could help his pain, I wanted to try and help his soul and his mind. He stayed strong as our dad and never let us see him sad, but I knew he (as a human) had to be wrestling the most difficult moments of his life.

Even though 3.5 years prior we were made “aware” that my dad wasn’t going to be one of those people who lived to 95, your heart, brain and life play tricks on you. You start to think, “well, of course that could happen – no one is going to break my spirit!” But when the call came that we were moving Dad to hospice everything became real. No matter how many times we talked about the fact he was likely going to pass away, I compartmentalized it, tucking it away in order to keep living and not be paralyzed.

Living far away from my dad, I wrestled with what was “right.” Should I just move back to Buffalo for a while? What about my husband, my seven-month-old, my job? What about me being me? Was that even important anymore? Was it okay for me to be happy? Then the guilt for whatever decision I did make – because none of them felt “right” at the time. Nothing felt right and after the fact I analyzed and reviewed all my decisions again.

The truth is there is no correct way to manage the death of a loved one - especially a parent who was always supposed to be the person you looked up to. Everyone’s journey is different, there is no guide, no book, no right or wrong emotion – so forgive yourself and be kind to yourself. I received a lot of great advice and my two favorites were: 1. Allow yourself to feel what you feel when you feel it, no judgment. And 2. No one wakes up and says “I wish I hadn’t spent more time with my dad.” More time visiting will always win out.

I went home a couple weeks after my dad’s prognosis. They said six-to-ten months. Spoiler alert: he barely made it two. I wrestled with when I should go back, how often, etc. I had just accepted a huge amount of new responsibilities at my job, we were launching two large initiatives and everything seemed to be happening at once. I remember my dad even said “why are you rushing to get here, I’m not going anywhere soon?” I had to lie and tell him that I was coming back for my mom’s birthday. I went, we had fun. He held my daughter, Emery, for the last time. Emery loved his cannula and we even got her her very own to play with and she loved his old school radio. We didn’t talk about “it” at the time. We were all still in denial. He was still sleeping on his couch. He had a two-bedroom place but my dad always loved sitting on the couch and watching TV. It was kind of the perfect place for him. It was his happy place.

A week later my mom said hospice felt I needed to go back sooner than Thanksgiving. I booked another trip, and then another. Then the hospital bed came. Dad couldn’t sleep on his beloved couch anymore and he would never hold Emery again. I helped my family move the couch, furniture and get him some other necessary equipment. He played “cups” with Emery. They both clapped their little plastic cups together over and over to make their own music. Dad always had the pink and blue ones and Emi used the green and yellow. Emery laughed and giggled at him from across the coffee table. My dad helped me sing ‘goodnight sweetheart’ while I put her to sleep in my arms so I could stay just a little bit longer. We brought him all his favorite treats, cinnamon rolls and Tim Horton’s coffee. I would bring him the Bran muffin that he began to love over the course of those two months. We’d have breakfast together and laugh at Emery as she was learning to eat solids.

I left Buffalo to head back to Denver on November 11th. Emery's 39th flight/plane. Dad was good, we all felt good that he’d be making it through the holidays. My next trip was scheduled for November 23rd for a full week over Thanksgiving. Every morning I talked to my mom on my way to work asking how it was going. He had his ups and downs, his blood pressure was dropping but no red flags waved by hospice nurses. I spoke to my mom on November 22nd. She was not able to see my dad in the morning but was going to go by later. He had a great breakfast according to my Aunt. Then around 3PM Mountain Time my mom called and I knew. I remember yelling into the phone asking him to hold on, telling him that Emery and I were coming the next day. I remember telling him he has to hear her first words, she was babbling and he needed to hear it before he left us. He yelled ‘I love you’ as best he could and my mom said she’d call me back. I quickly got flights for us that night and ran home to pack. We were eating dinner on our way to the airport when my phone rang. I looked down and saw the caller ID and new. I collapsed outside in the cold winter and sobbed.

How could I not be there? How could I have not made it to see him one last time and say good-bye? It was the longest and worst night in an airport and on the plane. I wanted to wear a sign that said “F-off my father just passed away.” Swollen eyes, crying Emery and nothing to console. Nothing to do but wait… but wait for what? To land and know I’d never see him again? What was really on the other side of that flight?

The most important things. Family, memories, stories, pictures and love. I don’t know what would have been worse. Seeing my dad in his worst state? Being able to be there for him like I really wanted, but seeing him in a way I could never forget? Or being thousands of miles away with no ability to do anything but feel empty.

Three months after my dad passed we lost my grandfather. We were shocked to learn in January that he also had cancer and it was everywhere. After learning how advanced it was we lost him about two weeks later. I don’t know what the world has in store for all the people impacted by losing these men so close together, but I do know that it gave me perspective on all that really matters. Always say “I Love You” to your family. Always take that extra drive or flight to visit them and cherish the moments and memories you are making. Look at the circle of life and you will find peace while you grieve.

Emery has been a saving grace. She reminds us every day of the continual circle that is life and brings joy to so many difficult moments. How depressed can you be on Christmas without your dad when you see the light in the eyes of a child or loved one? Take each step slowly and gently, you will wobble, you will fall and there will be drop offs you don’t expect. Feel what you feel, when you feel it – or it will creep up on you, promise. And know that they never truly leave us because they are a part of us.

“Unable are the loved to die. For love is immortality.” – Emily Dickinson

By Keith McWalter

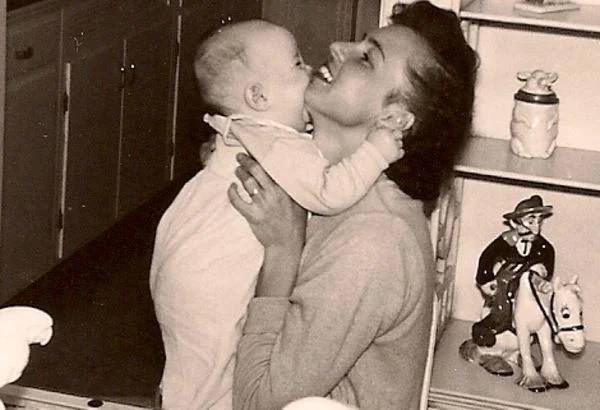

One Sunday ten years ago, my mother Alice and I sat together in the dining room of the retirement community to which she’d moved at my urging a couple of years earlier. “The Sequoias” was an appealing, campus-like complex of small apartments and common facilities on the San Francisco peninsula, about a mile from where I then lived.

My mother and I had lunch together most Sundays after attending services at the Presbyterian church down the road, where she sang in the choir and I often sat in the pews and watched her bobbing, red-haired head. She was 85 years old, lucid and sociable and, while delicate and careful of bearing, far from frail. I was going through a divorce and much of our conversation that day cycled between my tepid explanations of why this was taking forever and her muted puzzlement that two people like my wife and I couldn’t work out their difficulties, as though I’d come home with a sub-par grade on a particularly important standardized test (which, of course, I had).

As we chatted, she ate little, and complained of an upset stomach. I urged her to eat something anyway, as she never seemed to take in enough calories to fuel a hamster, let alone a mature woman. Later I walked her back to her little studio apartment, admired the new plantings outside her sun porch, and went home to watch some football.

That night my mother called me at home, late. She never called me, let alone late at night, seemed still to think that phone calls were the costly extravagance they had been in her childhood, to be resorted to only for the most pressing and practical purposes. She said her stomach felt much worse, and when pressed, admitted that she’d had diarrhea (a word that, to my knowledge, she’d never uttered to me before, and certainly not with regard to herself) and felt nauseous. She had no car, and had been unable to convince someone from the Sequoias to drive her the half-mile to the nearest supermarket for some Gatorade (which she’d been told she could “keep down”). I told her I’d be right over, and on the way stopped at the pharmacy and hastily bought a number of over-the-counter palliatives, some Tylenol, and the Gatorade.

I found her in her nightgown in her deployed Murphy bed, two simultaneous indiscretions she would never have exposed me to under normal circumstances. She looked pale, as well as embarrassed to have me putting my hand to her forehead. I felt no fever, and quizzed her about what she had eaten recently. The Sequoias’ medical clinic was closed for the evening, and when I offered to call a doctor and make them damn well open it up, she said no, she just needed something to drink and some sleep. I made her promise that if she felt no better by morning, she would call the medical clinic and get herself checked out. She submitted to this role reversal with some grumbling, and even allowed me to tuck her in.

The following day was a typically busy one in my office in San Francisco, and by late morning I had forgotten about my mother’s bad stomach, full as I was of professional self-importance. On returning to my desk after some trivial errand, there was a voicemail message from her, sounding a little feathery and strained, saying that she was being taken to Stanford Hospital and that she had been told that there had been an E. coli outbreak at the Sequoias. In a mild panic I called her apartment, got no answer, then called the Sequoias’ medical clinic and was told that no doctor was available and I should call back later. At this, lawyer that I am, I smelled crisis management, and bolted for the door.

I raced my car down the San Francisco peninsula to the enormous Stanford Hospital, and was told that my mother was in the ICU. I found her there in a room to herself, in transit between the bed and the bathroom for what I immediately understood from her pained expression and shuffling gait to be the hundredth time that day. She was in a hospital gown and slippers, and looked disheveled and not at all glad to see me. She was, by upbringing and disposition, an extremely modest woman. Her eyes never quite met mine, and she spoke in an irritated grumble. It dawned on me that she was humiliated to have me see her this way, having never been in a hospital in her life except to give birth to my brother and me and to attend to her sister when she’d had a mastectomy. I decided to stay out of her way for the moment.

I eventually located an attending physician who told me they would administer an intravenous drip to re-hydrate her, and that while blood samples had been taken to determine if E. coli was indeed the cause of her condition, results were not expected back for at least a day. This struck me as preposterously slow in the digital age, and I told him so. He shrugged. I asked about antibiotics and was told that these were never given in these cases as they only accelerated the release of toxins by E. coli bacteria. Clearly I had much to learn. I envisioned the little bastards spewing venom in their death throes as the amoxicillin washed over them. Kill them anyway, was my first thought.

At this point I was worried and angry, but not fearful. My mother was in the ICU of one of the great teaching hospitals in the world, with the most advanced research and equipment at hand. I thought of E. coli as something on the order of salmonella – something that could make you sick and maybe wish you were dead, but unlikely to be life-threatening. And my mother was not a sickly or weak-willed woman. I figured they’d send her home in a day or two and my job in the interim was to be available just in case she deigned to speak to me.

In her articulating hospital bed, Mom was more agitated than I thought warranted, still averting her eyes and responding to my obsequious questions with monosyllables. It occurred to me finally that she was scared, and didn’t want me to see it. I mumbled a few words of reassurance, but she would have none of it. With the intravenous drip stuck in her arm and her eyes drooping, I eventually kissed her on the forehead and went home for the night.

The day after my mother’s hospitalization I was on the phone to the Sequoias like a raptor on prey. I was again told by the medical clinic that my mother’s regular physician was “busy.” When she finally called back she said that she had no information on my mother’s condition because, she said, once a resident was taken to the hospital, the Sequoias’ medical staff no longer followed the case. I told her that sounded crazy to me, and that while she might think she had no further stake in my mother’s condition, I intended to hold her and the Sequoias responsible for it, so she’d be well advised so show some interest…..and so on, up to the point I slammed the phone down.

When it rang again, it was my mother, sounding confused and panicky, saying repeatedly that they “couldn’t make any decisions” about her care. I assured her that she wouldn’t have to, that I’d be right there, and asked her what decisions she’d been asked to make.

“Dialysis,” she said. I thought I’d heard her wrong, or that she was slurring, or hallucinating. I called my daughter Jessie, who was a law student at U.C. Hastings in San Francisco, and asked her to join me at Stanford Hospital.

On my way there I called my brother Craig back in Columbus and told him what was happening. He had already heard from my mother that she was sick, but was startled to hear that she was in the hospital. I explained things as best I could and promised to keep him up to date.

Jessie and I found my mother in her bed, pale and sullen and, again, withdrawn and uncommunicative in a way that seemed bizarre even by her exaggerated standards of modesty. When I finally got her to talk, she said she’d had a visit from her pastor from the Presbyterian church, and been humiliated when he’d entered her room just as she was being helped to the toilet for the umpty-umpth time that evening. “Don’t let anyone visit me. I really don’t want any visitors,” she said in a voice that gave me to understand that any moron would have known this in advance.

I soon got to the bottom of the mention of dialysis: an intern drew me aside and said that my mother was experiencing renal failure. As I had power of attorney under my mother’s living will to make medical decisions for her, they would put her on plasma-replacement dialysis only if I would consent to the procedure. My heart dropping to around my own kidneys, I said I would. But what, I asked with the first flutter of real fear, was causing renal failure?

The blood samples had in fact come back positive for E. coli, contamination vector unknown. I would later learn in some detail the effects of the bacterium in the human gut. It emitted a powerful toxin which, when absorbed into the bloodstream, caused platelets to coagulate en masse in a futile immune response. These massively clumping platelets soon choked any body part rich in blood vessels, such as the kidneys and the brain. The effect on the brain is something like hundreds of mini-strokes. This at least in part accounted for my mother’s lack of focus and refusal to talk -- she couldn’t focus and she couldn’t speak, because her brain was being asphyxiated. This would make her at least temporarily demented, but the renal failure was worse – that could kill her.

The hematologist in charge of my mother’s case had ordered full hemodialysis (a three-hour procedure, to be performed daily) in addition to plasma replacement therapy (another three-hour procedure, also daily). In essence, they were going to cleanse and replace my mother’s entire blood supply every day. Would I consent to this? Yes I would. But I wanted a meeting with all of my mother’s attending physicians the very next day.

The following morning, my daughter and I met with four specialists in a little conference room off the ICU. We sat around a table just as I had sat around countless tables like it in countless rooms like this one to discuss, say, a financing transaction or partnership taxation. But in this case, the topic was the likelihood of my mother’s survival.

The doctors told me that she had probably suffered extensive organ damage resulting from hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS, that disaster of the blood platelets), that some of it, including loss of speech, might be irreversible, and that the prescribed course of treatment was to continue the plasma replacement and hemodialysis for the next few days -- or weeks -- to see if her kidneys would recover and if any other organs showed signs of improvement. At this point I felt obliged to point out that my mother’s living will (not to mention my own knowledge of her preferences) ruled out “heroic measures,” and that a lot of what they were describing seemed to fall into the “heroic” category. The doctors responded that it was too early to tell if current treatment was having any effect, and recommended that the dialysis be continued for another few days.

I looked at my daughter, her eyes large and grave and very much like her grandmother’s in her youth. She had reached the age where she needed less to be sheltered from things like this than to be included in them – the beginning of that great tilting of the world that would end with her in my place and I in my mother’s. Better to let her practice this now. I asked her what she thought and she said that another few days made sense to her. I agreed and the little meeting broke up.

I called my brother again. He had been the one who had seen my mother for lunch every Sunday when she had lived near him, was there with her when my father had died (as I had not been), had sent her off to California and to me, his older brother, with what must have been a mixture of regret and relief. I had brought her to this place, and now she was dying. He was near-mute, far away, helpless. At least I was on the scene. I told him to consider coming to join me, soon.

I called my mother’s sister, Jennie, who lived in Phoenix near her daughter Becky. My mother and Jennie had been close throughout their lives, and Becky and her siblings Melanie and Kevin and my brother and I had all been kids together, regularly visiting one another’s homes across continental distances. We all thought that Jennie was the smartest person in the entire family: a feminist before the word came into common currency, a survivor of a dozen domestic disasters (ne’er-do-well husband who died young of emphysema, consequent decades of single motherhood, only son killed in a SCUBA accident, breast cancer, younger daughter lost to drugs and the street, you name it), eloquent letter-writer, bona fide MENSA member, her life was a saga to beggar fiction.

Aunt Jennie couldn’t have been clearer: Alice wouldn’t want to live like a vegetable. Alice wouldn’t want to be poked with needles and manhandled by orderlies. Alice would rather be dead. I understood and agreed, but said we had to give it some more time. She told me that Becky was planning to fly out to join me and Alice, and that was welcome news. I considered my cousin, in her forties and a clinical therapist, to be a rock of empathy and good sense.

The days blended together now. I no longer went to my office. I arrived at the hospital one day to find my mother, agitated and incoherent, with the dialysis technicians attempting to find a blood vessel in her body large enough to insert the large-bore needle necessary for the blood transfusions. After much struggle, as I cringed helplessly at the foot of her bed, they used a vein just below her neck and inserted a “permanent” needle portal there to accommodate the repeated transfusions and other injections that would be made.

She was only intermittently lucid now and had stopped speaking altogether, except for the occasional “yeah” or “no” and a shake of the head. She had been catheterized and outfitted with an adult diaper to deal with the chronic diarrhea. She was aware enough to know when she needed to go to the bathroom and would then hold her arms out to me to help her get up, like a little girl who is tired of walking and wants to ride in her parent’s arms. I would try to quiet her and get her to let go and simply endure the humiliation of soiling herself. My dignified, modest mother. I was grateful in a way that she could not speak, that we had no choice but to work through this in grim pantomime. When she quieted, I would drift out into the hallway and lean against the wall for awhile.

We entered the second week of my mother’s illness. News of the E. coli outbreak at the Sequoias had leaked into the local press. More than two dozen residents had become ill, and over a dozen had been hospitalized, most for a few days. Only my mother remained in intensive care. Suspicion had centered on a spinach salad that had been served an anniversary party at the Sequoias. I knew from that last Sunday lunch with her that she had attended that party.

The dialysis continued, six hours a day. A machine the size of a refrigerator would be wheeled into my mother’s room, an amiable technician would hook her up to the apparatus at the various ports and hoses sunk into her body, and the slow churning would begin. The technician pulled up a chair and read a magazine, peaceful as a monk.

Though she was not given any sedatives, my mother would appear to sleep throughout this process, as she did for most of the day. It was as though some natural anesthesia had kicked in to protect her from her mortifications, or her body was engaged in such an exhausting inner struggle that there was no energy left for the outside world. I had abundant time to study her in the act of sleeping, something I had rarely witnessed in my entire life. She would sometimes snore, but what struck me was that on the exhale her lips would bubble up for a moment before her breath would burst softly through with the sort of wordless noise she might have made when, alert and judgmental, she disapproved of something. Years later, coming out of an afternoon nap, I would catch myself doing the same thing, and remember her in her hospital bed with the sun striping the sheets through the half-drawn blinds.

My mother was still producing no urine. She had had no solid food in over a week, so there was discussion of inserting a feeding tube, either nasally or through her stomach wall. I said I would consent to the former but not the latter. This was the sort of fine calculus I’d descended to in trying to rationalize that we were not keeping her alive by the “heroic measures” she so abhorred. Soon the normal course of the plasma replacement would be run, though dialysis would have to continue in the absence of any perceptible renal function.

The insertion of the feeding tube did not go well. While the tube was inserted into her nasal passage without much difficulty, x-rays later showed that it had been passed into her trachea and lung. After another couple of attempts over many hours, this effort was abandoned. She was left with another indignity, a bloody nose, which I futilely dabbed at.

If there is a God and he has angels on earth, surely a large percentage of them are assigned to work in ICU’s. One nurse named Gina attended to my mother as though she were her own, washing her with a gentle intimacy I could never have managed, brushing her hair, speaking to her as though my mother heard and understood every word, seeming to understand my mother’s grunts and sighs, often simply sitting for a moment to hold her hand. She must have seen mortal illness and death a thousand times over, yet behaved as though each new body before her was a unique treasure. This broke my heart open as nothing else had, this simple, direct, brave caring of one stranger for another. I was and am in awe of Nurse Gina.

Then the bane of old people in hospitals arrived: chest x-rays revealed indications of pneumonia. The antibiotics that had been avoided in the early stages of her illness were now administered, and an oxygen mask was strapped around her face. She was slowly disappearing into a cocoon of medical apparatuses, and into herself.

Throughout these days my mother responded, if at all, only to the offer of water, which she craved continuously. This could be given to her only in the form of small bits of ice, which I would slip onto her tongue with my fingers in a way that reminded me uncomfortably of the gentle way a family dog would muzzle a treat.

Becky arrived from Phoenix, Craig from Columbus. My brother was speechless and undone to see our mother this way all at once and without the incremental deteriorations I’d witnessed, and could barely stand to be in her room for more than a few minutes. He’d keep disappearing and we’d find him down the hall, in the cafeteria, outside looking at the sky.

Becky – cool, assured Becky – clearly saw herself as a stand-in for her own mother, who was herself too ill to travel. She was the older daughter, responsible and successful – the female version, in her own family, of me. We’d always had an unspoken mutual understanding of the burdens of filial competence and, therefore, of each other, and we both recognized the irony (or was it simply logic?) that her own mother, having survived so much, including cancer, might at last survive her only sibling, my mother, who had enjoyed a vastly more comfortable and tragedy-free life.

Mom’s dialysis continued, and because she was agitated when conscious and would attempt to tear away the multiple intravenous lines running into her body, she was put under wrist restraints for much of the time. Her skin had always been thin and dry and bruised easily, and by now she was bruised over much of her body. Her forehead was papery and cool when we bent to kiss it.

The one acquaintance I had who was a doctor at Stanford showed up to discuss my mother’s condition with me. A lovely olive-skinned Pakistani with brooding brown eyes, she was a pediatric cardiologist (a doctor to the hearts of children, which struck me as a redundantly celestial calling), but had familiarized herself with my mother’s “charts.” She expressed the view that, while the dialysis and other measures were keeping my mother alive, the quality of life issues implicated in her case led her to conclude that the best course might be to make her as comfortable as possible and discontinue the life-supporting measures. The decision would be mine to make.

I’d known this was coming, but welcomed her confirmation that certain choices were no longer avoidable. The next morning we had another all-hands meeting with my mother’s attending physicians. Jessie had come down from the city so all of our family members were present. We all agreed with the doctors that the limits of any reasonably effective medical measures had been reached, and that all efforts should henceforth turn to trying to make Alice as comfortable as possible.

So they eventually cleared away the tangle of tubes from her poor reduced body except for the nasal oxygen tube and the intravenous, and started her on a morphine drip to ensure that she was in no pain. And we all sat around her for most of the day and into the evening and talked and brushed her hair and fed her chips of ice and put cold compresses on her forehead and prayed and told stories about her and all of us -- pretty much as I suppose people have been doing over their dying relatives for millennia. And still her battered but determined little godly machine of a body continued to slowly turn its engines.

A day or two later, Becky announced that she was going to spend that night in my mother’s hospital room. I protested weakly, guiltily glad to be relieved of another night’s vigil.

I went home and slept and was awakened by the phone around seven on what was a Sunday morning. It was Becky, saying that my mother had passed away an hour or so earlier. We all convened at the hospital and said our final goodbyes over my mother’s body. Then, oddly lighthearted, we all went into Menlo Park and had brunch at a sidewalk café. What had gone on the night before I never asked and was never told, but there was an ineluctable rightness to her strong sister’s strong child being present at the moment my mother finally let go.

It had been two weeks to the day since that last Sunday lunch with my mother. Later in the day I returned to the hospital to begin to deal with the practicalities of having my mother’s body removed and, according to her wishes, cremated. I walked into the ICU almost by habit and with a little shock found her room empty, the bed stripped, the body long gone. Why would it be otherwise, I thought, and yet how strange to see that little room, her and our final home, laid so bare.

Several lessons were unavoidable to me in the wake of my mother’s death: that no matter when death comes, it is sooner than we want or are prepared for. That the human body is a tough little machine that doesn’t give up life easily. That the mind inheres in the body, and the body absent the mind is not the person; that once deprived of the mind, the body reveals itself as a tenacious animal mechanism, not at all the holy vessel we make it out to be. That family and friends are, in the end, our only consolation. But also that the death of others – even those dear to us -- can serve, perversely, to reaffirm the fantasy of our own perpetual survival; and that few among us can, like Nurse Gina, stare death frankly and compassionately in the face and not look away.

A few months after my mother’s death, on a blustery Mother’s Day, my brother, my daughter and I climbed the high hill that stretches upwards from behind the Sequoias to the western headlands of the San Francisco peninsula. It’s called Windy Hill, and it’s a fairly arduous climb, but from its peak, you turn west and look out over the Pacific, turn east and take in all of San Francisco Bay. We scattered my mother’s ashes there. Not a bad place to come to rest, I’m sure she would agree.

Life goes on.

By Peter Russert

During the last few months of my mom’s life I had two main thoughts about her. First I didn’t want her to have to suffer any more. I prayed that her body would just call it a day, and slip away silently during sleep. At age 90 she was in chronic pain, and could no longer get out of bed. Failing kidneys, fluid buildup around her heart and in her extremities, chronic pulmonary distress—I don’t think I can even rattle off all her “co-morbidity factors” as her doctor termed them. Thank god my aunt and I had finally found an assisted living home near the ocean in Venice, Florida that my mom had been willing to move into. During the last couple of decades she'd insisted on living alone in her own little apartment but she'd taken so many serious head-splitting falls over the previous two years that I was honestly surprised she’d survived. True to form, she’d tried to conceal all these episodes from me. Often I had to find out about them from my aunt, or the hospital. As I sat by her bedside in Venice she’d say things like, “I don’t understand why I’m still here. How do I keep going?” Of course with large stocks of hydrocodone right at hand my question was “Why do you keep going?” But that’s another matter.

My second thought was that her story would never be written. Not that her biography would have mattered much to anyone except me and perhaps a few of my cousins or their children. She didn’t set any world records, or marry anyone famous, or amass a fortune. But she did grow up in a pretty unusual and unusually batty (or was it just “colorful”?) family in Reading, PA. And that was only the beginning. I tried several times over the years to get her to at least sketch an outline of her story, bought her a couple of digital recorders in hopes that that would make it easier. But I wouldn’t have been surprised if she’d turned to me once and said, “Honey, some of those things I just don’t want to live through again.” Some of them were incredibly painful. I know, I lived through them with her. But about her childhood, the beginnings of her journey, I only got snippets and slices. So in an effort to try to grasp their deeper meanings I probably invented some myths. And yet when I tried some of these ideas out with one of my aunts, she said, “Yes, I think you’re probably right.”

There seemed to be two big forces at work in my mom’s life. The first was the lifelong search for a place, a role, a clear purpose. She was born Caroline Jean Vernon in 1922, the fourth of six children, to parents who were impossibly detached and remote, not to mention ill-suited to one another. I could poll my aunts up and down the line (I have): “We raised ourselves.” Jean, as they all called her, was sickly as a child. Her older, more self-assured sisters and brother had their own interests; her two younger sisters formed a tight bond that constituted its own little world. I think my mom was always baffled about where she fit in, and thus who she was in this peculiar drama. Who were her teammates? What part was she supposed to play? She had a strong love for her older brother, Stephen, who never minded including her in whatever he and his buddies were up to on weekends or summer evenings. “C’mon, let her tag along. She’s not going to be any trouble.” I inferred that the rest of them were too busy fending for themselves; if you didn’t, no one else was going to.

Of course, this is only one side of the Vernon family portrait. My mother and my aunts could tell endless farcical stories of their childhood—the word “circus” fit their collective life just fine. (Here’s a mere taste: my mom delighted in telling me about how my grandmother lived in books and loved to do nothing more than retreat to the library and read, regardless of the chaos throughout the rest of the house. While she read she enjoyed eating a well-know local brand of chocolates. My mother and her sister Lolly liked to sneak into the library to sample these candies. When they took bites out of ones they didn’t like so much, they’d neatly put them back into their wrappers in the box. These were dubbed “spitbacks,” and to underscore my grandmother’s abstracted nature Jean told me that Granny would pop a spitback into her mouth while reading and never miss a beat. I often got the impression that their family life was just a huge mashup of mischievous bits like this.)

The second force in my mom’s life was an enduring sense that no matter what she tried or what she chose, things were going to go wrong. I don’t think she cultivated this sense of doom, or wanted anything to do with it. Stuff just happened. And kept happening. Kept pounding the message of futility into her until she capitulated. Maybe bad stuff happened to people who were uncertain of their places or senses of purpose?

In her late teens she fell deeply in love with a local boy named Howard Lutz. As I heard the story, he was just as crazy about her. They talked about getting married—at least until the day he arrived at the house and told her that while he was still very much in love with her, he had to marry another girl who “couldn’t survive without him.” He “couldn’t let her down.” I always took this as code for “Jeannie, I’ve gotten another girl pregnant—what can I do?” My Aunt Lolly said Jean was devastated. But it couldn’t end there, of course. Not long afterward Howard enlisted in what was then known as the Army Air Force (this is the beginning of World War II), and was killed in a training accident in Pensacola. If you flip through my mom’s papers you’ll find old sepia-toned photos of him. In one he is emerging from a swimming pool, laughing, his dark hair slicked back. And he’s beautiful, by any standard. I could easily understand how deeply smitten—and wounded—she’d been.

It was bad enough to have the outside world throwing defeat at her, but her own mother got into the act. I’d known in my youth that my mom had spent time in Coast Guard during World War II; I’d seen the pictures. But her stint in the service took on a different significance once I’d grasped her craving for a mission. She loved the Coast Guard. She took her share of hazing from the guys she was stationed with in Palm Beach, but a letter of commendation makes clear that she manned her radio post with valor during a hurricane. She spoke glowingly about her commanding officer and how much he’d taught her, what a great mentor he’d been. Perhaps there was romance there too? “He took me all over Miami, and really opened my eyes to what was happening there.” After the war she returned to Reading. Meanwhile her commanding officer had sent a letter to her encouraging her to re-enlist. She told me she would have done it in a heartbeat. But she never saw the letter, at least not until long afterward. Her mother had read it herself and kept it from her—because having a meaningful life with the possibility of advancement was a bad thing for her daughter? This floored me.

Then, somewhere in this time frame, her father killed himself. I never knew what to make of this episode, or its impact on my mom in particular, because it was always shrouded in mystery. He was shrouded in mystery. Was he terminally ill, or did he fear, as I once heard, that he might be following his own mother’s footsteps into insanity, or…? Or he was simply depressed? The event had one kind of impact on two of my aunts who heard the gunshot in the library, and found him with a bullet in his head. But my mother was en route home at the time. She never wanted to say very much about it.

She soon returned to Miami, fatefully enough, to become a flight attendant for Eastern Airlines. But she was chronically airsick on those old DC-3’s. “The stewardess who was too busy throwing up to help anyone else,” she laughed. “Well, there you have it…” That lasted a year maybe. Back on terra firma she met my dad, got into the hotel business with him, and had me. And yet while I was still a toddler she was obviously beset with doubts. To the point of crisis, apparently. Once again my grandmother came into the picture. My mom told me she just wanted to pack up, grab me, and escape from Florida. She asked her mother whether she could return to Reading to stay with her until she sorted things out. My dear old granny told her, “Absolutely not. You made your bed down there; you can lie in it.” This sounded incredibly cold and vindictive to me when I first heard it, but I figured out later that it simply reflected my grandmother’s old-school conception of marriage as an ironclad social contract. No matter how miserable you thought you were, you just couldn’t run away. You had to tough it out.

And so she stayed and toughed it out. In fact she had a second child with my dad, a daughter named Anne. She may have bought the idea, as I know some parents did in those days—and maybe still do—that having another child would help settle her marriage and bring more normalcy to our dysfunctional collective life. Not this time. When she was about three my sister somehow contracted meningitis. I don’t know how long she was really sick, or how meningitis works, but it seems to me that she was in trouble for a couple of days, and then suddenly died at home in her bed. I’m sure my parents were clueless at first about the seriousness of the illness—I’m guessing it seemed like flu—but on the Saturday my sister died she was vomiting some very dark stuff, and my mom knew she had to be seen by a doctor. She called my dad. He told her to bring her to the hotel he managed on Miami Beach; there was a “good doctor” who was a guest who was willing to look at her. The good doctor misdiagnosed the illness—I half want to write “of course.” That was early afternoon. When my dad got home at about six, my mom asked him to go upstairs to check on my sister. By then her lips and her fingertips had turned blue. I know; I saw her body.

I won’t say much more here about my mom’s grief—my parents’ grief; it doesn’t need elaboration. Or even her unbearable sense of responsibility for the loss of someone so young and vulnerable. She carried this guilt with her for the rest of her life. But beyond this, she seemed in her own mind to just get further affirmation that whatever she loved was fated to go wrong. That whomever she loved was going to be taken away from her. That she lived under some sort of curse.

Our family more or less fell apart from that point forward. But Jean went on. I realized over time that she had a very deep capacity for love and even for forgiveness. She married again, twice. Both husbands died during the marriages, but on the whole they were very happy times. (Don’t worry, we covered all the jokes about “No more marriages, no more dead husbands!”) Jean was in love, she got to travel widely, make a lot of new friends, and feel fulfilled. But there is another scene that comes to mind here—this was in the mid 1980’s when she was taking care of her own dying mother. In fact the scenes of my mom ministering to my grandmother at her bedside are uncannily similar to my own presence at my mother’s side just before she died. It was a little different though in the sense that my mom had done nothing in her life that I could be bitter about. My grandmother had never been a real mother to her children. She had overruled, and even manipulated my mom, maybe more often than I knew, and certainly with some arguably tragic consequences. Did my mom ever think, “You wouldn’t let me come home; if I’d been able to, I never would have lost a child!” And yet I remember my mom doing everything possible to make her mom comfortable. My grandmother was 93 by then, and had been silenced and incapacitated by a series of strokes. She could do little more than lie in bed and stare quizzically. My mother brushed her hair, gave her sponge baths, fed her, caressed her, and spoke to her as if she were a little girl passing through a childhood illness. I don’t know why Jean, among all her siblings, took on this task, but it was quite amazing to observe.

I never gave my mom the love she deserved. I was too busy getting away. I grew up feeling a strange (and illusory) sense of autonomy, and disconnection from both of my parents, their anger, quarreling, and visible unhappiness. Several times my mom used that infamous phrase, “I always thought you were the real adult in the family.” Of course I didn’t really want to have to parent my parents, although once or twice it seems I actually had to break up fights and send people to neutral corners. On the other hand, I was glad to escape dependency on both of them as much as I could. I think my mom got this; I’m not sure she even had to bear it stoically. She might easily have said to me, “Hey, getting away is what we do. Maybe its just in our genes. Your dad was the youngest in his family, and he couldn’t wait to escape from home. Even I tried to run away as a child…” which was an amusing story in its own right.

My mom not only understood my desire to escape; in a weird way it gave her strength and happiness. In her myth, I was the one who made it out alive, the one who proved she had done something right. She was sure I had “made it,” that my life was some huge success story, and while this was mostly illusory, I had no interest in puncturing the illusion. Over the final few months she’d told me countless times, “I don’t want to disrupt your life; I don’t want to be a bother. You’ve got big responsibilities in your own family.” I said, “Don't be absurd,” and got on a plane to head to Florida whenever I needed to. We had never seemed very close emotionally, and certainly not outwardly affectionate, but in her final days, I was by her side, holding her hand, bugging the hospice nurses to give her extra doses of morphine. And telling her I loved her. Once, during her last hour or so, her eyes flashed open, and she more or less cried out, “You were my first born and always closest to my heart!” Then she drifted right back into unconsciousness. I was startled by this, especially in light of my sister. But I think I knew what she meant.

By Steven Morrison

I have this friend. Of sorts. (Labels can be so confining.) He’s one of those beings with whom I share one of those connections that is just so deep and rich and expansive and fun. It’s the relationship in which I feel most at home, where I am fully me, recognized as me, celebrated as me, loved as me. I am seen and heard and understood. And I have never laughed more with another living soul.

It’s complicated. Kind of. We don’t live in the same neck of the woods anymore and he’s probably best described as a free spirit. I try to keep tabs on him but, frankly, he’s far better at keeping them on me and will often show up, magically, with a perfectly timed and deeply relevant message. Like he did a few weeks ago.

On that occasion I was feeling at my wit’s end, worn down, exasperated about something that was going on (not my usual m.o., but it happens) when he suddenly swept in, finding me at the home of some other friends, while I was enjoying alone time outside on their deck. Nice! By the time he departed, not 15 minutes later, I knew without a doubt that the solution to my circumstance was as at hand and that he would even help bring it about. Thanks!

Accustomed as I have become to the whims of his comings and goings, I’m always completely blown away by how our connection is instantly re-constituted when he does show up. On that day, out on the deck right after he left, I felt saturated with love that was so expansive and which was so magnificently commingling itself with layers and permutations of joy and peace and awe and gratitude that I needed a moment. I hid out in the restroom for a while because I couldn’t contain all that juicy, emotional, life-affirming energy and make dinner at the same time.

It’s hard to put a label on my friend because most everyone would say he’s dead. And he is. Moreso at this point, than the proverbial doornail. Dead, dead, dead. It has been more than eight years since his cancer-ridden body, his name, his personality, the various roles he played -- son, brother, friend, cousin, grandson, nephew, uncle, confidante, employee, jokester, and, in my case, soul mate and life partner -- all got buried. Still, he is most definitely not dead, just ask him. And our relationship was not snuffed out when he died, it just changed form.

Have you ever had a romantic relationship come to an end, then develop into a friendship? I certainly have. Several times. In that situation, sure, the romantic form of the relationship dies as does the sexual aspect. (Usually!) But focusing on what has died is largely unproductive. Meanwhile focusing on the inherent connection – the love that doesn’t die – allows other aspects of the love to emerge and develop. And presto change-o. The relationship changes form.

When my friend’s spouse survived a brain aneurism that left him physically and mentally incapacitated, the ways in which they could experience and share the love they had for one another disappeared. Died. No doubt about it. Yet her willingness to stay present and open to other ways of sharing and experiencing their love allowed the form of their relationship to morph into something else and it did. And her heart grew bigger.

It was no different when the love of my life up and died when he did. I endeavored then, quite consciously, to expand my own capacity to feel and experience the love that used to come through his beautiful human body, wondering if and how it could happen without that body (and whatever else went with it). And what do you know? Mission accomplished. Our soul mate, romantic, physical, 3D human relationship is definitely dead and gone but it has morphed into something else. It has endured and it is growing. Still. Just in a different form.

I’ve come to believe that when our loved ones depart this plane, some things die, for sure. Yet much does not die. I’ll fall on a sword to argue for the notion that what doesn’t die – the love – is infinitely more important than what does die. And that our willingness to explore that love and what it can show and teach us will expand our human experience(s) in ways we never imagined.

Friend? Spirit guide? Guardian angel? Soul mate? Spiritual brother? The label means nothing while the experience means everything. Despite his death several years ago, our relationship journeys on. We are still connected, we can still communicate and instead of dwelling on all that we had, I can fully and wholeheartedly experience all that we have.

By Kim Vigier

The metal feels cold in my hand as I push down on the handle, yet comforting and warm from all of the memories it holds. The simple act of mashing potatoes for tonight’s dinner leaves me choking back tears and trying to put on a brave face in front of my little girl... The potato ricer was my grandfather’s and a recent acquisition since my grandmother finally sold their home and moved into an apartment, a year and a half after his death. I’m the only person in the family who ever used it besides him and it’s become one of my most prized possessions.

They say it’s supposed to get easier as time goes on but in my case, it’s not true. It’s gotten worse. My pop, as I called him, had been sick for over a decade and was affectionately known as the cat with nine lives. Multiple end of life scares year after year but it was never his time. In the last year of his life, I pushed him, more than I ever had, to fight…. to fight to make it to my wedding and then to hold on a bit longer to meet his first great grand child. He did both, with the same brave face I had known all 33 years of my life. And a month and a day after my daughter was born, he was gone, taking with him a piece of my heart I will never get back.

Maybe I didn’t grieve as much as I was supposed to because the past eighteen months have been filled with so many good “firsts” that I forgot about the bad ones… My daughter’s first Christmas was also the first Christmas I’ve ever spent without him, her first birthday nearly marked the one-year anniversary of his passing and so on.

Now, with his and my grandmother's house being sold, I’m starting over. I will no longer take the quick fifteen-minute ride over to their house just to say "hi." Or call and see if they need anything from Costco since I will be around the corner. My grandma lives farther away now and as much as her new home is lovely, it’s not the same. She started fresh, with new furniture and paint and a different zip code and I hate it. It just doesn’t smell like my grandfather’s house.

I hold on to memories and share stories with my daughter. There’s even a picture of him in her room and every morning she points to it and says “Poppy.” Yet I’m still left struggling with how I can honor this man who was the one constant male figure in my life. I spoke briefly at his funeral, a reading the pastor had selected which rolled off the tongue quickly amidst the flowing tears. It didn’t mean anything to me and all I’m left with from that day is regret. This man had never let me down and in the final moments, I was unable to share with the world who he was in my eyes.

I wanted them to know that my grandfather thought he was a failure. That he had spent decades questioning why he chose to open a Wetson’s fast food restaurant instead of McDonald’s. That he and my grandmother struggled financially each month but he still managed to squirrel away $500 for my wedding gift, a check that pained me to cash but I did it anyway as to not want to embarrass him. My grandfather had enormous regret about things in his life and felt he was leaving this world with nothing to show.

What I wanted him, and every one in the church that day to know was that my grandfather was exorbitantly wealthy, not in money, but instead with the love of his family. A family consisting of his wife of sixty two years, four children and their spouses, and six grandchildren and their partners. A family that rallied every time he was ill to gather at the hospital. A family that came together for Sunday football games and a dish of macaroni. A family that took yearly family vacations. A family that called him each and every day just because... A family that never missed one Christmas together in my entire lifetime. And a family that at the end, surrounded his bedside as he took his final breaths and left us. A family that carried out each and every one of his last wishes, including having his tombstone inscribed with his favorite quote “Family is life’s greatest gift.”

I’m expecting my second child in January and while I consider myself blessed to have a healthy baby, whether it be boy or girl, a secret part of me prays every day that I will have a little boy to carry on his name. More than that though, my sincerest hope is that my grandfather will live on in my unborn child and my daughter and that somehow, even though his heart stopped beating, this new life affirms that he’s still very much alive in all of us.

By Barbara Trainin Blank

New Year’s Eve has never been a particular favorite: the noise, the traffic, the excessive drinking. More particularly, there was the year I was an overseas student and my entire section of the city went dark. Another time my college boyfriend broke up with me, and that same night my grandmother passed away.

But perhaps no New Year’s Eve was more memorable than the one of 2000. Or more traumatic.

Technically, it wasn’t New Year’s Eve. The call came in the morning, about 8 o’clock. It was from my father. His voice sounded hollow, hesitant. Since he more often expected to be called than calling, I was apprehensive…

For good reason. Binny (my first cousin once removed), and his wife, Talya, 34 and 31, respectively, were dead. They had died in their car, while driving home from Israel to the Territories.

That would have been tragic enough. Sadly, there are way too many road accidents in Israel. Drivers there are crazy! But this was no accident. Shooters had caused my cousin to lose control of the car and overturn. They had been alerted by a lookout that a car with Israeli license plates was approaching.

Binny died instantly. Talya was taken to the hospital and died soon after.

I was too overcome with weeping to consider what many asked me later: had Binny been targeted? He was the son of an assassinated right-wing Knesset (Parliament) member and himself a radical.

His mother thought otherwise. But he had been targeted. His wife had been targeted. Not for their specific identities or even their politics but for their nationality and religion.

I was sad and angry.

They weren’t the only victims, as even those who die peacefully in their beds ever are. Their son was safe; they had dropped him off in school on the way home. But their five daughters were in the car. All were injured, one seriously. She was hospitalized for a long time.

I grieved for Binny and Talya and for their children. The trauma, yes, and the terror, of losing both parents, suddenly and violently, are not something most of us can understand. Especially before 9/11, when terrorism had yet to hit home to Americans.

How could children that age comprehend, or accept, that the only way their parents were coming back home was in a coffin? How long would their journey to healing be, and how successful? Would they ever be OK?

My heart went out to my cousin-by-marriage, Libby, who had lost a husband and now a child. A daughter-in-law she was fond of like a daughter. It was a second call I had to make to Libby in which the “right thing to say” didn’t exist. But a child’s death was even worse than a husband’s. Is there anything worse? Especially when the death is sudden and violent. My heart wrenched as I picked up the phone.

There was nothing I could do with my grief except empathize with the suffering of others. When someone in the town we used to live in lost a son to a bombing incident at an Israeli university, I was one person who could understand. It resonated deeply when she described a support group she attended for bereaved parents. The participants went around the room, indicating how they had lost their children. Nearly every case fell into two categories—cancer or car accidents. Then her turn came, and she he told the group her son had been blown up by a bomb. Everyone just stared. Finally one person broke the silence with, “That’s the worst.“

There often isn’t a whole body to bury. Friends and family members are left not only with a sense of overwhelming grief but of vulnerability. That is, after all, the goal of terrorists. To make people think it could be anyone of them. I was struck with a sense that something is very wrong with the world. Some friends and family members tend toward bitterness and anger. Some might even contemplate revenge. Certainly, they can become obsessed with redress, bringing the perpetrators to justice. I’m a mild-mannered person who did not share my cousins’ politics, but certainly, none of those reactions was alien to me. They were my cousins, after all. They were human beings. Living life.

I am very tired of the killing. My family had paid the price of hatred and random violence. I could not understand people’s obsession with guns or the seeming tolerance of mass shootings. (Libby’s cousin on the other side had also been killed by terrorists, particularly brutally, while defending, unarmed, a holy site.) I’m frustrated by the inability of the two sides in the Middle East conflict to reach any kind of lasting, meaningful agreement. (On the other hand, the region is rife with armed conflict among people of the same religion.) I read a book in which a rabbi who had been stoned while walking through the marketplace of the Old city of Jerusalem set out to find and understand his would-be killer. I had no such reaction — it saddened but did not enrage me that one of my cousins’ killers was freed in a prisoner exchange. I simply wished he’d forswear violence, but doubted it.

When a loved one dies, you may feel like screaming: Don’t you realize how special this person was? In the case of terrorism, that desire to cry out intensifies: Don’t you realize how full of potential this person was? Don’t you realize what it’s like for six children to be orphaned? Why can’t everyone just stop killing? Sometimes there is nothing left but to pray: May there come a day that people of different nationalities, races, religions, sects, genders, and sexual identities learn to live together. Spare the bullets and the bombs.

By Jeudi Cornejo Brealey

Mom was a complex woman. Her true vocation, life calling and gift was as a mother. She’d mother anyone around her, no matter their age or size. No matter whether they were own children, or someone she barely knew. She’d even mother our father! Once he teased her, saying “Honey, for goodness sake, are you going to cut my meat for me, too?”

As we grew older, we kids would often chafe at her s-mothering as we were now adults, but it was her way of expressing her truest self. I saw this clearly when I had my own twin boys. She intuitively knew how to care for these infants, when I hadn’t a clue. Perhaps this is why she had five children. Babies were what she knew best and she was able to express her love and tenderness to someone less vulnerable than she.

She was not the soft, tender, snuggly mom that you see on TV, having heart to heart talks with her children. She didn’t verbally express her emotions well. Though there were moments of this sentimentality, by and large, her nature was that of a mother lioness, teaching her cubs to fend for themselves in a tough world.

Mom may not physically give you a long lingering hug, but instead she might symbolically offer you something cozy and cuddly. I remember that for years, every Christmas she’d give each of us a set of Long Johns to keep us warm in the winter. My brothers would all get Pendletons, too, making them look like a crew of lumberjacks. We might also get a scarf and gloves. Looking back, I think this was so that she could still feel like she was, at least, symbolically still holding her children’s hands and hugging us.

Mom may not give you a long lingering hug, but she’d slip you a $20, waving off any protests by saying “Put some gas in your car, or get something to eat!” Or, she send you home with a bag of tamales or a container of menudo saying “I can’t eat all this. You take it. My refrigerator is so loaded up”, as if we were doing her a favor by emptying it.

About the same time that Mom stopped driving, the home shopping network launched on the television. Mom loved it. She especially loved gadgets and was always ordering something new that she’d seen on TV. When you would visit, she’d beckon you into the guest bedroom, that was now really her gift dispensing room, stacked high with QVC shipping boxes. She’d apologetically offer, “Well, I don’t know if you’d want this, but, I saw it on TV and I thought you could use it”. Then she’ d gently hand you a gift bag with some recycled tissue paper haphazardly tucked around a QVC package.

More often than not, it was an item that you never thought you needed, much less needed to own. But to my mother, it offered the promise of so much more: It was an amulet to protect her loved ones against the harshness of the world. It was a solution to solve a menacing problem. It was a time saver, so you could enjoy life more and work less. It was a hug wrapped up in a QVC package. It was love.

One year, she gave me a three-way-tool, in case I was ever trapped in my car and needed to escape. It could break the windshield, tear through a seatbelt and illuminate my escape route, all at once. Never did I consider such a thing. But Mom did.

She was a constant worrier. She worried so much that she often couldn’t be present in the moment, concerned about something that may or may not happen in the future. One year, I gave her a copy of a book called “Meditations for Women Who Worry Too Much”. Not missing a beat, next time I visited, she gave me a copy of the companion book: “Meditations for Women Who Do Too Much”. Mom worried that I was overdoing it.

As we both grew older, she’d give me motivational and inspirational books on tape and lectures to encourage me on my own path. She may not be able to express her emotions, but she always found a gift or a Hallmark card that expressed it for her. One of my childhood memories is of her bedside stand, where one drawer was devoted to stationery. In it she always kept cards for all occasions, ready to send. I loved looking at these cards and I especially loved receiving them.

Mom liked being prepared and organized. She liked things to be useful and put away and in their place. She’d always get rid of “junk”. She was always giving things away. She wasn’t particularly sentimental. Or so I thought...Till after she passed away.

You see, Mom had a trunk locked away in the old playhouse. A steamer trunk the size that could easily accommodate two to three stowaways. As a child, I remember that from time to time, Mom would open it and sneak a thing or two inside. I always wanted to peek inside, and she’d chase me away, saying it was just a hope chest. Even in my 20s, she’d chase me away. I never knew what treasures were inside, till after she made her transition.

The contents inside revealed that she had saved each of our lifetimes of childhood memories: Christening gowns, beloved stuffed animals, baby bracelets and shoes, elementary school artwork. There she had stored away every report card, show program, school photo, love letter and greeting card she had ever received. A lifetime of treasured memories and emotions and vulnerabilities stored away and protected, just as she wished to protect her own loved ones. It truly was a hope chest, stored with symbols and objects representing a lifetime of love and hopes for a positive future.

After Mom made her transition, I was going through the nightstand where she kept her Bible, in the drawer just above the stationery drawer. I was looking through in hopes of finding something to provide solace to me. There, next to the Bible was the book I gave her. I never knew if she ever read it, but as I flipped through the pages, it opened to this bookmarked passage:

“Sometimes our primary form of sharing our love for our children is worrying about them and being aggravated with them when they give us an opportunity to worry. It helps to remember that when we experience fear and aggravation, this is an opportunity to share our love and caring”. Next to it, there was a meditation: “Love comes in many forms. One of them may be dealing with our own feelings, so we can show what’s under them to those we love the most”.*

What my mom loved the most were those who shared their lives with her: her family and friends. When she suffered the aneurism/stroke that led to her passing, some were saddened that they weren’t able to see her one last time and say goodbye. But really, there was no need for this remorse, for she knew she was loved and had a lifetime full of saved greeting cards to prove it.

Mom loved fiercely, like a lioness. She lived her 88 years on her her own terms: Smoking till the end, living in her own house till the end and mothering till the end. Even from her coma, she stubbornly refused to submit to death till she was assured of her cubs’ welfare and once she was satisfied, she peacefully drifted away to the next bold adventure.

Mom loved fiercely, like a lioness. She may not have let her tender side show very often, but she kept tokens of her love in QVC boxes, ready to dole out at the exact moment, like a secret antidote to whatever was ailing, or troubling you. She wanted to outfit you against the harshness in the world, and to make your life easier and guide you onward through life.

I still keep that tool next to me in the car, not that I think I’ll ever need to use it, but as a reminder of my mother’s fierce love.

*Quote from “Meditations for People Who May Worry Too Much” by Anne Wilson Schaef, Ballantine Books, New York, c 1996

By Elisa Adams

Death is finality. It brings tears and sorrow to the hearts of the ones left behind, sometimes consuming them. But what if that isn’t the case? Is there something wrong with you when your loved one leaves and there is no sorrow, no yearning, no missing?

Yes there were times of joy, fun and laughter, but they always came with a price. You learned what not to ask for and how to behave to stave off the rage that would burst through. What made it so hard was the unpredictability. The randomness that made it devoid of explanation time and time again left a young child confused and bewildered.

“What did I do wrong?”

“I shouldn’t have said that,” or “why did I ask for that?”

“I should have gotten a B instead of a B- and then it would be right.”

Always reviewing the daily events for all the possibilities of the things I did wrong. Hence my role in the family was the peacemaker. I became acutely aware of people’s behavior and tried to anticipate their needs. Having everything just so, as to avoid arguments. I would polish the silver, intensively clean the whole house, and make many a “Betty Crocker” dinner with the table set in high fashion. But every time, with any kind of conversation, within minutes arguments would ensue. They worked two jobs for several years. Stress levels were high. My brother and I were left to babysit each other. I would often re-arrange the furniture with the magical hopes of a child, thinking it would help change the energy and everyone would be happy in the morning. Ha! When I awoke, all the furniture was back where it originally was. That was telling. Did anyone ever query me to understand why I took on such an endeavor?

There was never respect from my father; I was his stupid daughter. Women really didn’t have a place of power in his world; actually we didn’t have a place at all. That theme haunted me for years before strength came. I was 33 when I could begin to stand up and express my feelings with less need for his acceptance. I tried that on for a while, but it was hard and would backfire through the next couple of years. I came to a new realization… He was not the father that I wanted growing up, nor the father I wanted at that time. There was never a conversation about life, or a batting around ideas. It was a monologue of what I “should” do according to him. If I didn’t behave in that manner, the screaming escalated.

Trying to change him wasn’t working, so I tried a new strategy. I decided to simply cut ties with him, to not speak with him for some indefinite period of time. Possibly, until a time when he would begin to understand. It was clear to me that understanding may never come and yet, cutting ties would make my world more peaceful. So I let him go.

I made the pre-emptive strike with my brother. I told him in June that I would not be at the family Christmas if our father was invited, nor would I do anything on our father’s birthday or father’s day. All of this was the price of letting him go. The first Christmas was hard. I met with pleadings from my brother to attend and I had to stand my ground.

This went on for 3 years. Then one April I received a call from my father at my office, asking if I would treat him. He had been in a car accident, hit his head and had terrible headaches. I told him I would have to think about it and I would get back to him. It dawned on me that I could treat him like my other patients in my chiropractic office, with care, compassion and non-attachment. So I invited him in. I sandwiched him in at my busiest times to ward off lunch or dinner invitations. And this went on for months. He would question my patients in the waiting room as to how they felt and if I was a good doctor. They would often come in scratching their heads asking who was that guy in the waiting room? I responded with, “One of my crazy patients.”

With this exploration of his, he was seeing my role in life and my importance, but for me it was a moot point. I had already lost my father and he was irretrievable. His narcissism was his nemesis.

When I got the call (years later) that he had a bladder infection that wasn’t being helped with antibiotics, I knew right away that he had a tumor, and found a urologist for him to see. What I didn’t know is that he had Stage 4 bladder cancer. I realized he would need help navigating the medical muck and mire, and that I could midwife him to his death. In my mind, I was offering my time to care for another human walking this planet. I immediately went to Florida to research, investigate and set up his healthcare team. By April it was clear he needed to be back in Boston. The next four months, I (consciously) took on another fulltime job. Again researching and setting up care here. Traveling to see him was two hours round trip, without traffic. First it was 2-3 times a week and then 5-7 times. I set him up with various groups, The Ride to get him back and forth daily to the hospital for radiation, VNA, and then ultimately hospice.

Opportunity came for me to say all the things I wanted to during that time. I thanked him for the good and told him my version of my upbringing, the honest truth. And it was liberating. Mostly because it didn’t matter what he said back, his opinion was just that and it was not valuable to me any more. I said my piece and I reclaimed my power. During the time since the car accident he would tell others and me that I was his angel. I am glad he felt that way. Yet for me those words couldn’t change what I was robbed of in my youth.

When time came to go to the hospice house, his final decline was rapid. Two days of semi-consciousness and one day of unconsciousness. That night my daughter and I went to see him. We were told that he was irresponsive the whole day. She walked in and said in a very loud voice “Papu, we are here, Mom and I,” and he tried hard to open one eye. He mumbled, “I love you both,” and those were his last words. He died the next morning.

He scarred all of us with his narcissism, but somehow in the end we still had love. I feel complete with him. For myself, I was happy to assist with his last caretaking needs, and now I am totally free. No tears, no longing, no missing…just freedom and peace.

By Josh Leskar

I had my first mudslide when I was 22 years old.

At least that's what I tell my parents.

Back home in Florida, we had this neighbor - Gregg "Mud" Lewis - and every time I returned from college for the holidays, he would invite me to have a drink with him at his favorite bar, J. Alexander's.

Gregg was a regular at J's. On almost any given night, you could walk through the door, hang a right, and there he was at his table; the last round booth on the left. Surrounded by his loving girlfriend, neighborhood friends, or the staff smiling at his presence, Gregg recognized essentially every face in the place. If he didn't, he must have made it a point to change that as quickly as he could, because he had the uncanny ability to converse with just about anyone within the establishment walls.